10. Climate responsibility, eco-anxiety, and perception about governments

Authors:

Leonardo Becchetti, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”

Francesco Salustri, Roma Tre University & UCL

10.1. Introduction

10.1.1. Individual actions for the environment: key for the transition, still costly

Climate change is notoriously cause by human activities and, therefore, citizens-driven actions to modify their behaviours and fight climate change represent an essential part of a complex solution. The International Energy Agency has recently recommended the transition to a circular economy, the adoption of low-emission technologies, the substitution of fossil fuels with renewable or nuclear energy sources, the promotion of sustainable mobility alternatives, and the replacement of fossil fuel boilers with heat pumps, among other measures (Bouckaert et al., 2021).

Changing behaviour, however, may be costly at both individual and collective level. Environmentally responsible actions may be more expensive, longer to implement, and they may require coordination among citizens. However, people may also play a pivotal role in facilitating the success of the necessary transition through their consumption and investment choices.

Given the importance of responsible consumption and investment, also highlighted by the Goal 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals, a large body of the literature has explored the determinants of individuals' willingness to pay for environmental sustainability. Among the socio-economic characteristics, not surprisingly education and social capital have been found as key drivers. More specifically, Kalkbrenner and Roosen (2016) have shown that trust, social norms, and environmental concerns have a positive influence on individuals' willingness to participate in energy communities. To further understanding environmentally responsible actions, empirical evidence has focussed on the link between declared willingness to act for the environment and their actual behavior. While earlier studies have found that stated willingness to pay overestimates actual willingness to pay (Brown et al., 1996; Seip and Strand, 1996), more recent studies using experimental methods indicates that the two measures do not substantially differ (Carlsson and Martinsson, 2001; Zabkar and Hosta, 2013).

10.1.2. Citizens-driven solutions as a multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma

The citizens-driven solutions to the climate thread can be model as a multiplayer prisoners’ dilemma, where people can choose whether to act responsibility, this choice may be costly, and all citizens and the environment will benefit from higher number of responsible actions. As strategic interactions, people make ecological choices based on what they know about other people choices. An insightful characterisation of games which model climate negotiations has been provided by DeCanio and Fremstad (2013). The authors highlight the conditions that may make the climate problem similar to a prisoner's dilemma or a coordination game. A similar approach has been followed by Becchetti and Salustri (2019), who modelled environmentally responsible choices using a social dilemma framework and discussing key variables that let mutually responsible actions constitute a Nash equilibrium. Other research have also used a game theoretic approach: for instance, Magli and Manfredi (2022) emphasised the inherent prisoner's dilemma nature of ecological interactions when short- and long-term preferences do not match, and Alvarez et al. (2019) have used cooperative game theory to inform prevention and management strategies of river flooding risks.

Our analysis relies on the model as in Becchetti and Salustri (2019) and aims at empirically test whether eco-anxiety and confidence in other governments effort to fight climate change have an impact on personal responsibility towards climate change. The prisoner’s dilemma hypothesis predicts that self-interested people are more likely to free ride should other actors behave pro-environment. According to this hypothesis, if people beliefs other governments are acting well against climate change, their personal responsibility should be low. Similarly, if people are worried about climate change, they should feel themselves more responsible to act ecologically.

The rest of the analysis is structured as follows: the second section explains the methodology, with a description of the dataset, and the econometric model adopted for our study. The third section illustrates the results of our analysis. The last section concludes.

10.2. Methods

10.2.1. Theretical model

10.2.1.1. Data

We use the data from the 10th round of the European Social Survey (ESS Round 10). These data collect information on a representative sample of adults living in Europe about their attitudes towards the environment. The sample includes approximately 32,000 respondents located in 19 countries and the relevant variables for our analysis are captured by the answers to the following questions:

-

Responsibility: “to what extent you feel it is your personal

responsibility to reduce climate change?” (From 0 = not at all to 10

= a great deal); -

Eco-anxiety: “how worried are you about climate change?” (Not at all

worried, very worried, somewhat worried, very worried, extremely

worried); -

Governments: “how likely governments in enough countries take action

to reduce climate change” (0 = not at all likely, . . ., 10 =

extremely likely).

In addition to these key variables, the dataset also collects several socio-economic characgteristics, such as sex, age, income, education, job status, marital status, and household size of the respondent. Moreover, the survey asks a set of questions regarding preferences and satisfaction (namely, political preferences, whether people have voted in the last election, health satisfaction, and income satisfaction), and we also exploit this information for our analysis. The interviews have been conducted between 2020 and 2022.

10.2.1.2. Descriptive statistics

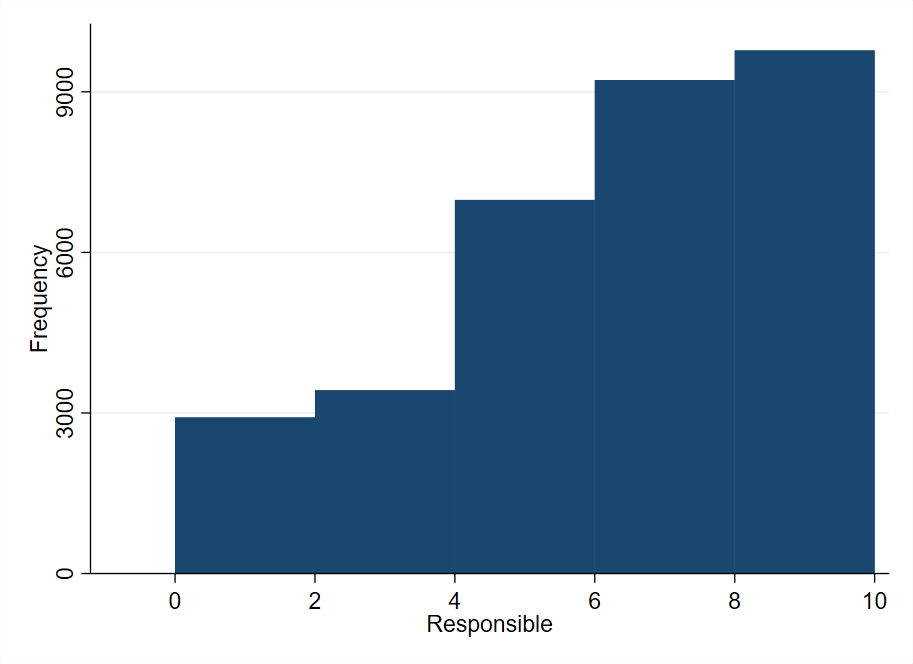

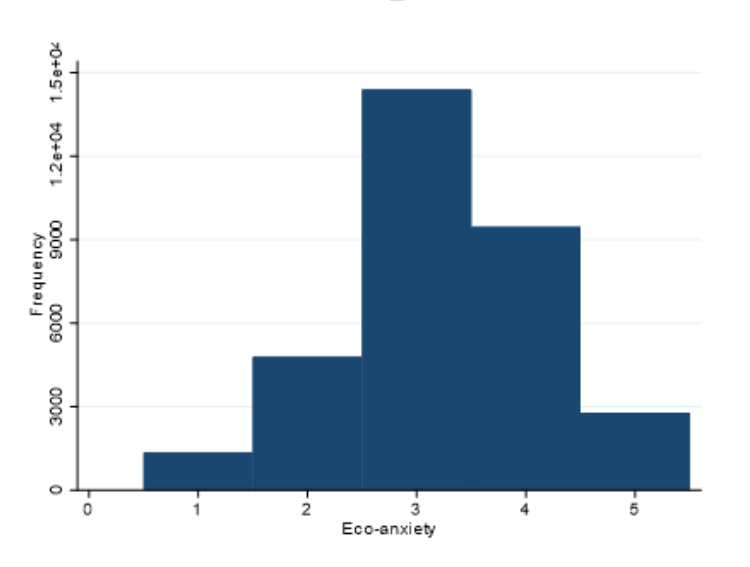

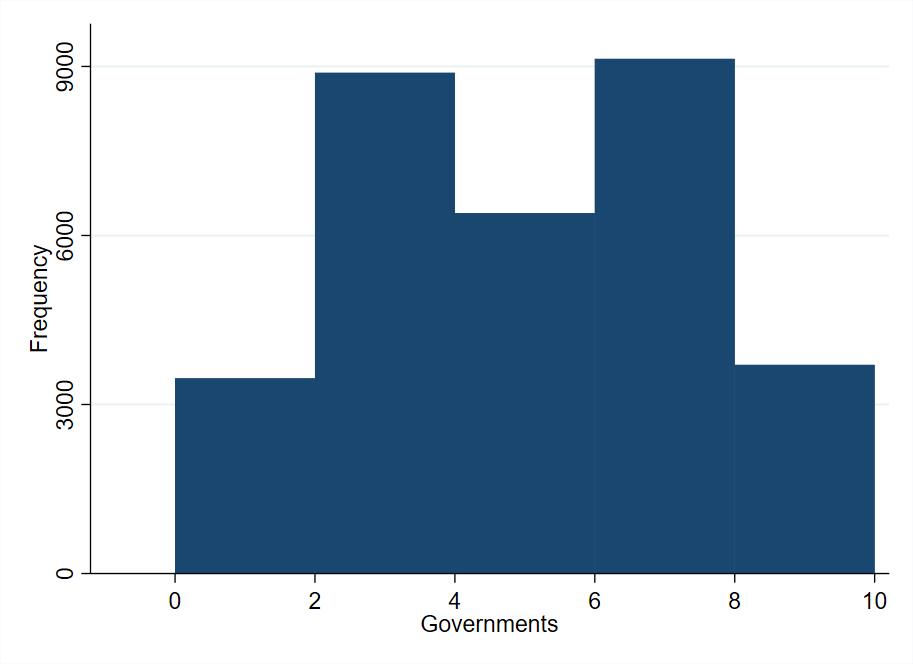

Figure 22 shows the distribution of our variables of interest. The large majority of the respondents feel responsible for reducing climate

change (Figure 22 , A) and anxious about climate change (Figure 22 , B). Differently, the responsibility of other governments is almost normally distributed (the variable has been recorded into 0-4, 0-7, or 0-10 likert scale for different countries and has been normalised into 0-10, and this explains the lower observation for the mid-value 5).

Figure 22 Distribution of Responsibility, Governments, And Eco-Anxiety

A

B

C

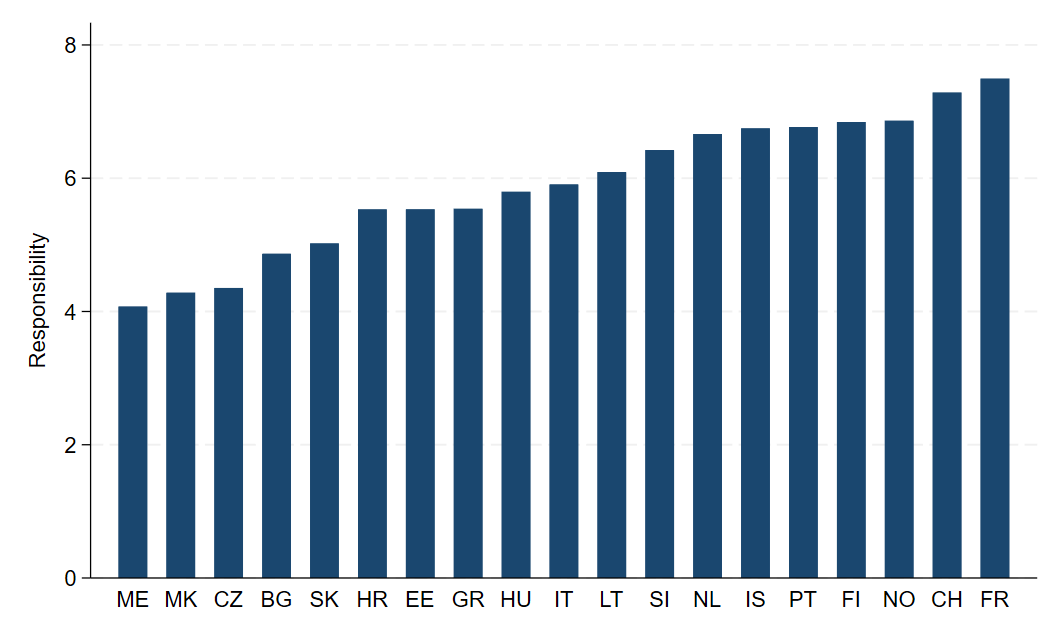

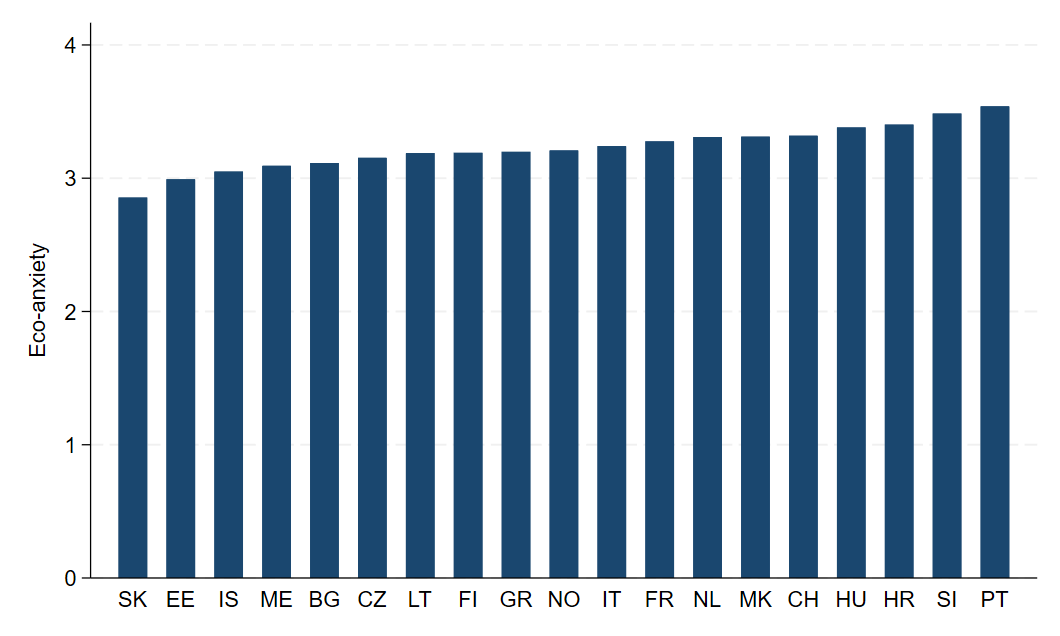

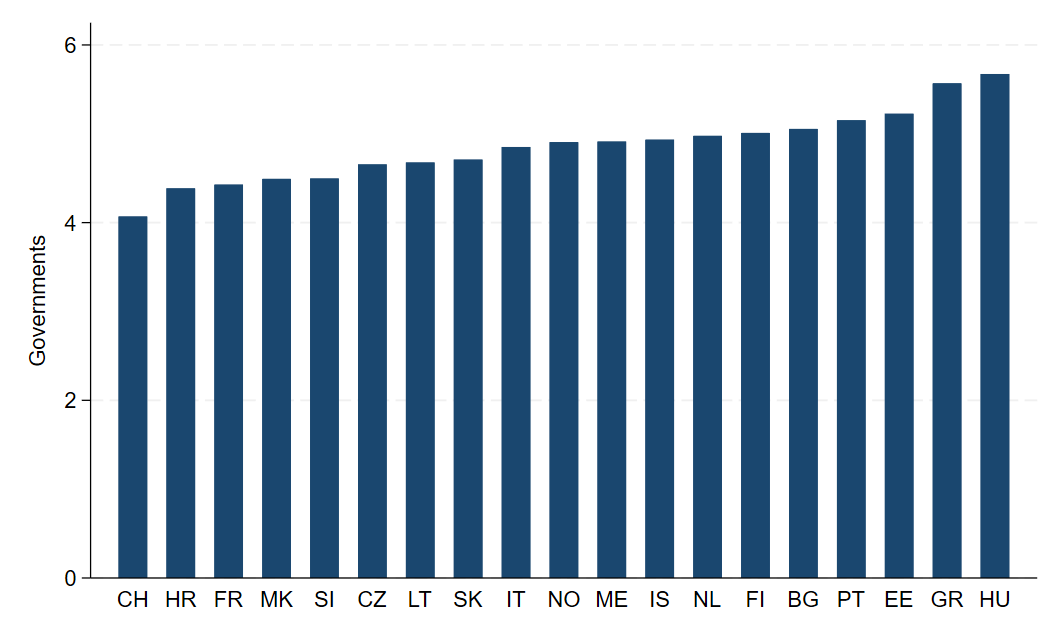

Figure 23 shows the average values fo our variables of interests by country. Responsibility displays a large heterogeneity, with people in France and Switzerland feeling more responsible and people in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Czech Republic feeling less responsible, on average. The other variables show less heterogeneity overall, with some differences between the extremes, though. People in Greece and Hungury believe more than those in Switzerland that other governments are acting enough to reduce climate change. With respect to econ-anxiety, Portugal and Slovenia have the highest values and Estonia and Slovakia have the lowest ones.

Figure 23 Country Average of Responsibility, Governments, And Eco-Anxiety

A

B

C

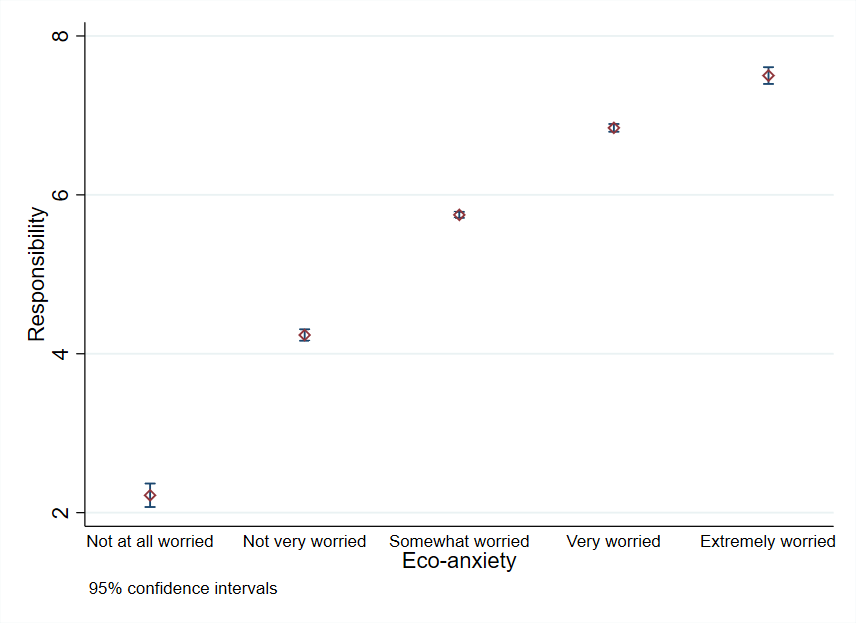

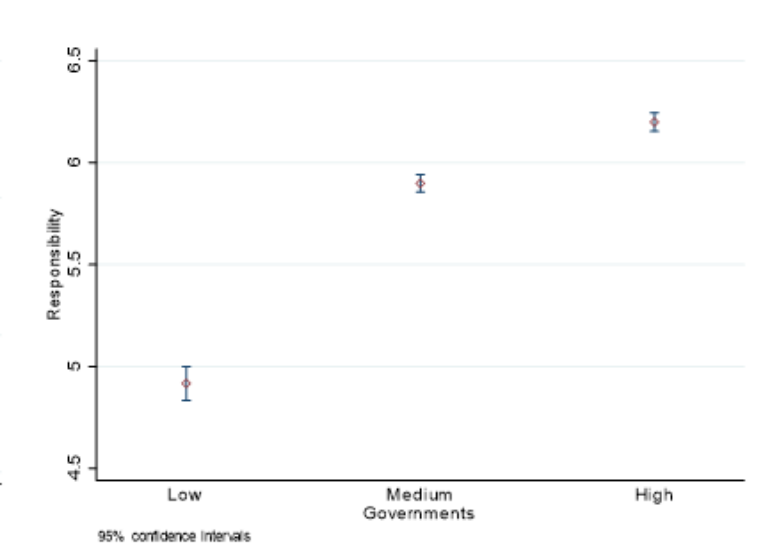

A deeper inspection at the role of Eco-anxiety and Governments in shaping Responsibility feeling is provided by Figure 23. We notice that the more worried people are, the more responsible they feel about climate change. This is consistent with the self-component in our theoretical model. Interestingly, when we look at the Governments variable, we observe that the more people believe government are acting well, the higher they feel responsible. This contradicts the free-riding option that people may perceive higher when other governments are already fighting against climate change.

Figure 24 Responsibility by Levels of Eco-Anxiety and Governments

10.3. Econometric model

To test the effect of Eco-anxiety and Governments on Responsibility, we run the following linear model.

Responsibilityi = b0 + b1Worriedi + b2Governmentsi + bhSocioeconomici + bkPreferencesi + bcCountryi + ui

where Socioeconomic captures sex, age class, education, income, job status, and marital status, Preferences captures self-assessed health, income satisfaction, political preferences, and participation to the last election, and Country include country dummies.

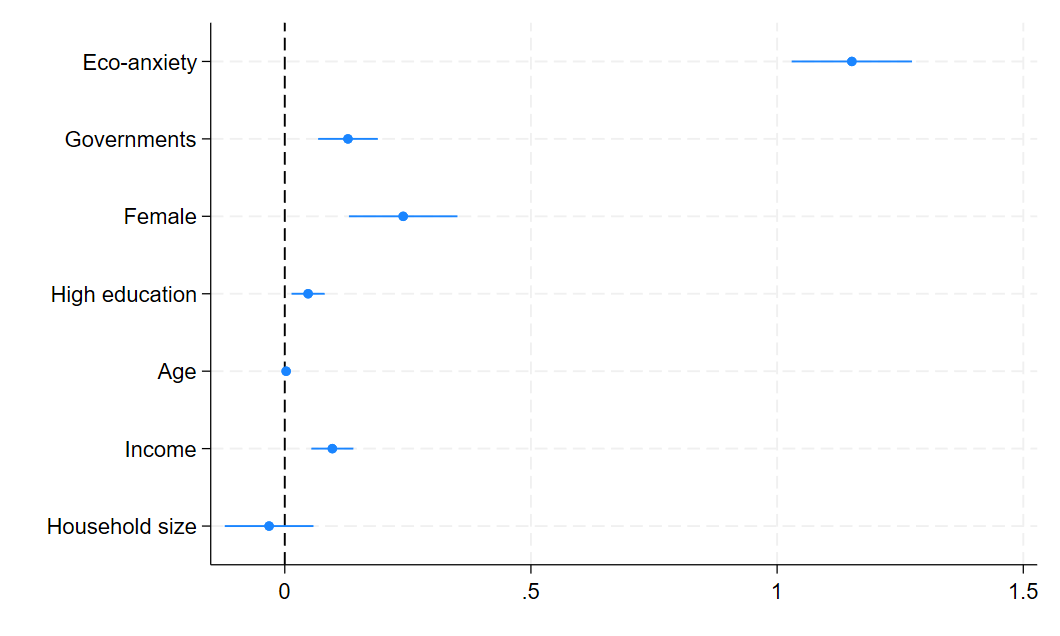

Figure 25 shows the estimated coefficients of the main explanatory variables. The results for the two variables of interest, i.e., Eco-anxiety and Governments, confirm what found and discussed at descriptive level. First, eco-anxiety is positive and statistically significant, suggesting that the more anxious, the more responsibility people feel. Second, the coefficient for Governments is also positive and statistically significant, and this invalidate the free-riding hypothesis that the more likely people perceived governments are acting against climate change, the lower responsibility they feel for themselves to act.

Among the socioeconomic characteristics, females and highly educated people are positively associated with higher responsibility, while age does not play any significant role. Income also plays a significant and positive effect on Responsibility, though very small in magnitude.

Figure 25 The Determinants of Responsibility

10.4. Conclusions

In this study we have analysed the impact of eco-anxiety and perception about other government effort in tackling climate change on personal responsibility toward ecological action. We have found that both eco-anxiety and perception about government effort have a positive and statistically significant effect on feeling responsible to act against climate change. These results partially confirm the theoretical free-riding hypothesis postulated by game theoretical model of ecological actions. Our results have relevant policy implications. First, increasing government efforts and better communicate it have significant positive externalities on ecological actions of the people. Second, the more people are aware about the climate threat, the more they feel responsible and are likely to act ecologically. This calls the whole scientific community to improve communication about the risks of climate change and therefore let people feeling more responsible through their everyday actions.

10.5. Chapter references

Becchetti, L. and F. Salustri (2019). The vote with the wallet game: Responsible consumerism as a multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma. Sustainability, 11(4), 1109

Bouckaert, S., A.F. Pales, C. McGlade, U. Remme, B. Wanner, L. Varro, D. D’Ambrosio, and T. Spencer (2021). Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. International Energy Agency Report

Brown, T. P. Champ, R. Bishop, and D. McCollum (1996). Which response format reveals the truth about donations to a public good? Land Economics, 72, 152–166

Carlsson, F. and P. Martinsson (2001). Do hypothetical and actual marginal willingness to pay differ in choice experiments?: Application to the valuation of the environment. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 41(2), 179–192.

DeCanio, S.J. and A. Fremstad (2013). Game theory and climate diplomacy. Ecological Economics, 85, 177–187

ESS Round 10: European Social Survey Round 10 Data (2020). Data file edition 3.0. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. doi:10.21338/NSD-ESS10-2020.

Kalkbrenner, B.J. and Roosen, J., 2016. Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: The role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Research and Social Science, 13, 60–70.

Magli, A.C. and P. Manfredi (2022). Coordination games vs prisoner’s dilemma in sustainability games: A critique of recent contributions and a discussion of policy implications. Ecological Economics, 192, 107268.

Seip, K. and J. Strand (1996). " Willingness to pay for environmental goods in Norway: A contingent valuation study with real payment." Environmental and Resource Economics, 2(1),91–106

Zabkar, V. and M. Hosta (2013). Willingness to act and environmentally conscious consumer behaviour: can prosocial status perceptions help overcome the gap?. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(3), 257–264.