5. Private Sector Funding of the SDGs

Authors:

Ketan Patel, Force for Good

Christian Hansmeyer, Force for Good

At the halfway point to the 2030 target date of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, it is increasingly clear that the world is not on track to meet the targets set in 2015. Slow but steady progress across multiple goals, in some cases over decades, has been undone by the global pandemic, current macroeconomic crisis and war in Europe, with c.100 million people slipping into extreme poverty, nearly 200 million more people suffering from chronic hunger, and 100 million more children falling below minimum reading proficiency since the start of the pandemic. And, with the world’s current energy, food and security challenges risking pushing back key SDGs even further.

These reversals have a significant impact on the SDG’s funding gap, a gap that has been further widened by the war in Ukraine, resulting in food and energy crises, global inflation, and accentuated migration. Further, recent estimates following last year’s COP26 meeting on the near-term costs of funding global Net Zero point to significant spending increase requirements, exacerbated by the roll-over of continued underfunding in 2021.

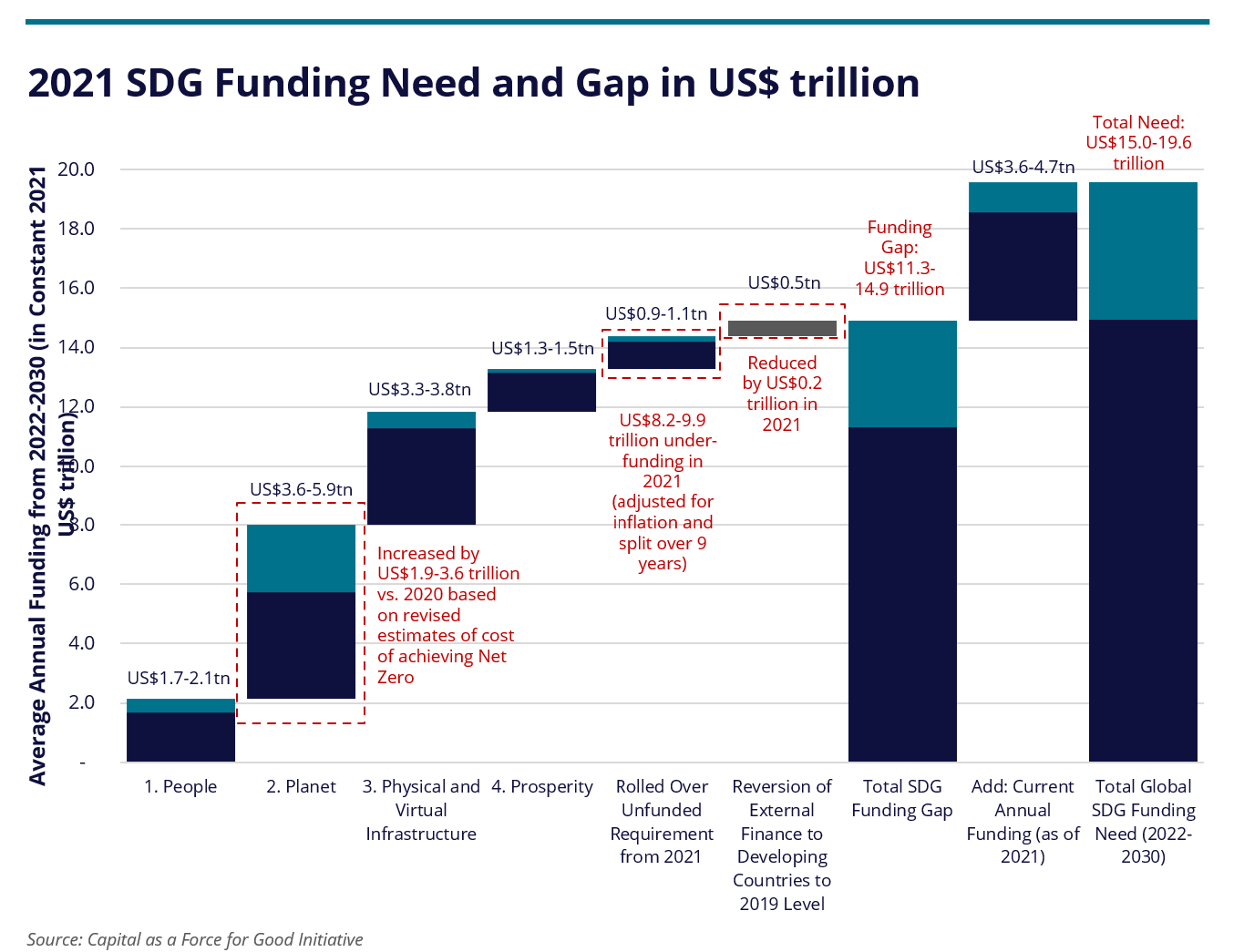

As a result of all these factors, the annual cost of funding the SDGs has increased by US$3-5 trillion over and above the previous most recent estimates[1] to a current total of c.US$15-20 trillion annually, an increase of c.30-40%. The recalculation estimates a total cost to fund the SDGs of US$135-176 trillion to 2030 (Graph 1[2]).

Graph 1 Updated SDG Funding Need

Given that only approximately a quarter of the current total need is being funded, the annual funding shortfall is estimated at US$11.4-15.0 trillion, a c.35-50% increase over the same estimate the year before, with a gap of US$103-135 trillion to 2030. The implications are substantial. Given that the world is currently investing 4-5% of its GDP annually towards the SDGs, fully funding the goals would require spending to increase four-fold to 16-20% of 2021 GDP, and this is clearly not likely without other priorities being sacrificed at material scale.

The importance of the SDGs in underpinning peace, prosperity and freedom in the world is well established. The achievement of the SDGs within the next decade is critical for the world to avert the crises that will result from over-exploitation of resources, extreme weather events, pollution and biodiversity loss, poverty and inequality, political and social strife, and mass migration.

Moreover, the total cost of US$135-176 trillion to fully fund the SDGs represents c.30%-40% of the world liquid assets, which total US$450 trillion.

Governments and public institutions control US$167 trillion, or 38% of the world’s liquid assets, most of it in advanced industrialised economies. However, most of this capital is non-discretionary, required to fund domestic public services like healthcare, welfare, pensions, and education, as well as to maintain existing infrastructure, leaving only a fraction for sustainable development, most of which is required in developing countries. This leaves much of the SDG’s funding need in the hands of the private sector, which collectively controls US$275 trillion in assets.

While private sector corporations collectively control c.US$60 trillion in assets and may well make considerable strategic investments that impact the SDGs, the vast majority of private sector SDG funding is likely to occur in the form of financial investments. The global finance industry controls or administers nearly US$400 trillion in total assets for public and private asset owners, with institutions deploying capital in their capacity as asset managers, wealth managers, pension managers, lenders, and proprietary investors.

Among other private sector participants, the tech industry has a significant role to play in closing this gap. An analysis of the mass deployment of technology estimates that technology can make a significant contribution to bridging this gap and can also reduce the cost to fund the SDGs by US$55 trillion, solving for c.40% of the SDGs, given that technology is key to 103 of the 169 targets associated with the SDGs. However, this still leaves a significant gap to close and that has brought much focus on the finance industry.

5.1 Finance industry leaders SDG financing increasing significantly

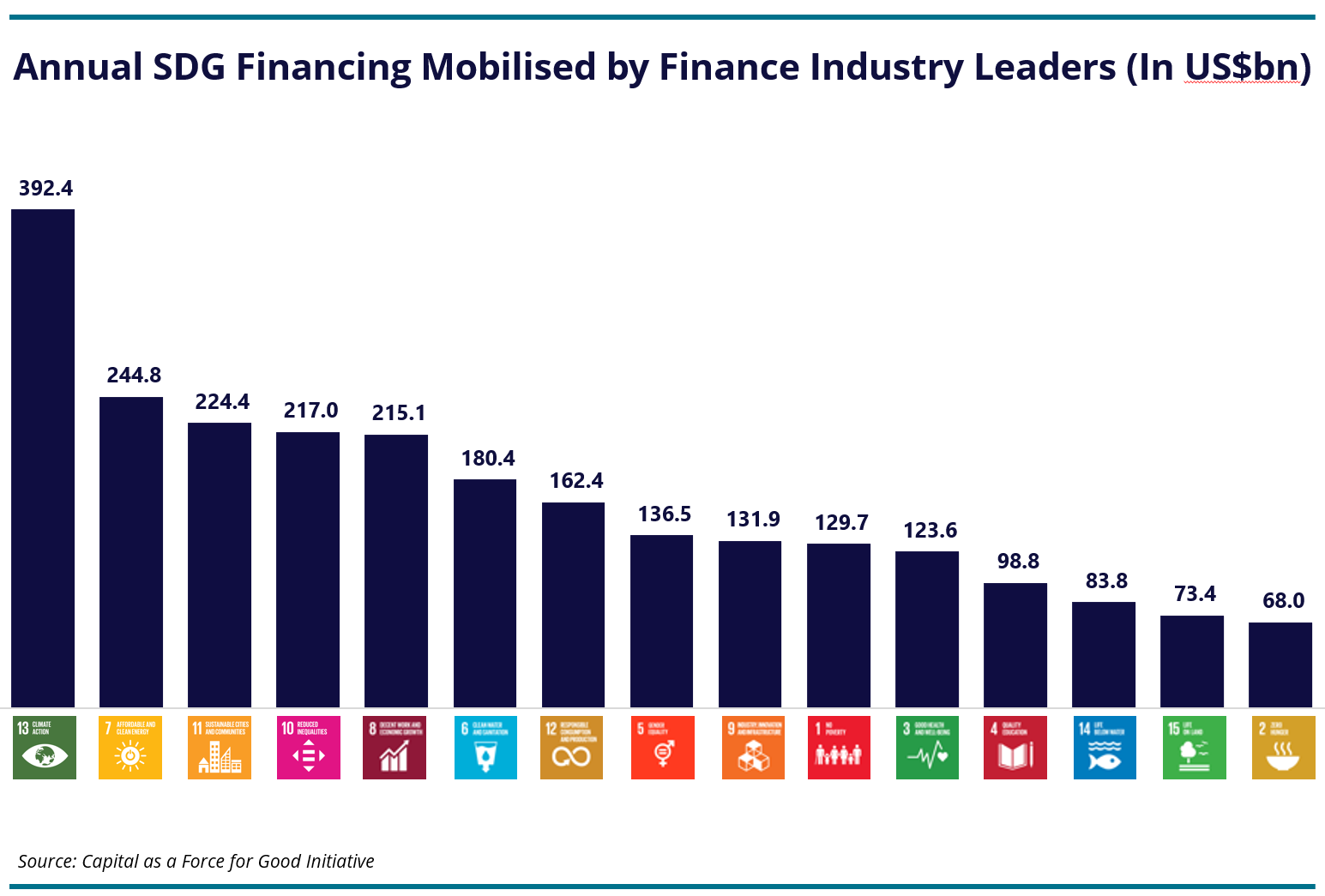

Examining the sustainability funding activities of 125 of the world’s largest financial institutions reveals that there is a large common ground between them in terms of their focus on ESG, sustainable finance and stakeholder engagement. For 40 of these financial institutions (which are the public companies with more standardized reporting), their activities reveal that private sector engagement with the SDGs is increasing in both scope and scale (Figure 7). Having deployed a total of US$2.1 trillion in SDG aligned financing in 2020, this group of companies increased their funding by 20% in 2021, deploying a record US$2.5 trillion. The detailed breakdown of these leaders’ initiatives and commitments points to the increasing breath of their engagement over time (Graph 2).

Further, these companies’ SDG focus during the past year has continued to diversify. While climate change and renewable energy continue to be areas receiving the most attention, institutions are broadening their focus on SDGs relating to human development, prosperity, and broader planet related goals. The data shows institutional focus increasing across almost all goals, with a significant rise in engagement with SDG3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), as well as SDG 14 (Life on Land), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), pointing to the fact that leaders have recognized the need for broader engagement with the SDGs, and have identified or developed a broadening set of engagement models to allow them to participate in their funding.

Figure 7 Finance Industry Leader SDG Engagement 2022 vs 2021

However, despite these increases, private sector engagement on the SDGs as a percentage of the total capital remains tiny and is highly skewed to a few SDGs backed by strong business cases and high returns potential, with three times as many institutions focused on SDGs like SDG 7 (Clean Energy) and SDG9 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), rather than less focused on(and less profitable) goals such as SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 14 (Life Under Water).

In terms of the actual funds deployed to specific SDGs during the past year SDGs, funding to virtually all goals increased, with only SDG 13 (Climate Change) and SDG7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) seeing absolute declines reflecting the greater diversification in finance industry leaders’ SDG spending priorities. The two goals’ share of total spending accordingly decreased from 40.2% in 2020 to 25.7% over last year. The distribution of the increased spending maps closely to the increasing prioritization of key SDGs laid out above. The biggest absolute spending increases of US$146 billion and US$142 billion went to fund SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), respectively, while SDGs 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), and SDG9 (Industry, Infrastructure, and Innovation) received funding increases of US$60-80 billion each last year.

Graph 2 2021 SDG Funding Breakdown by Industry Leaders in US$ billion

5.2 Finance industry leaders SDG financing is increasingly aligned with critical SDG funding gaps

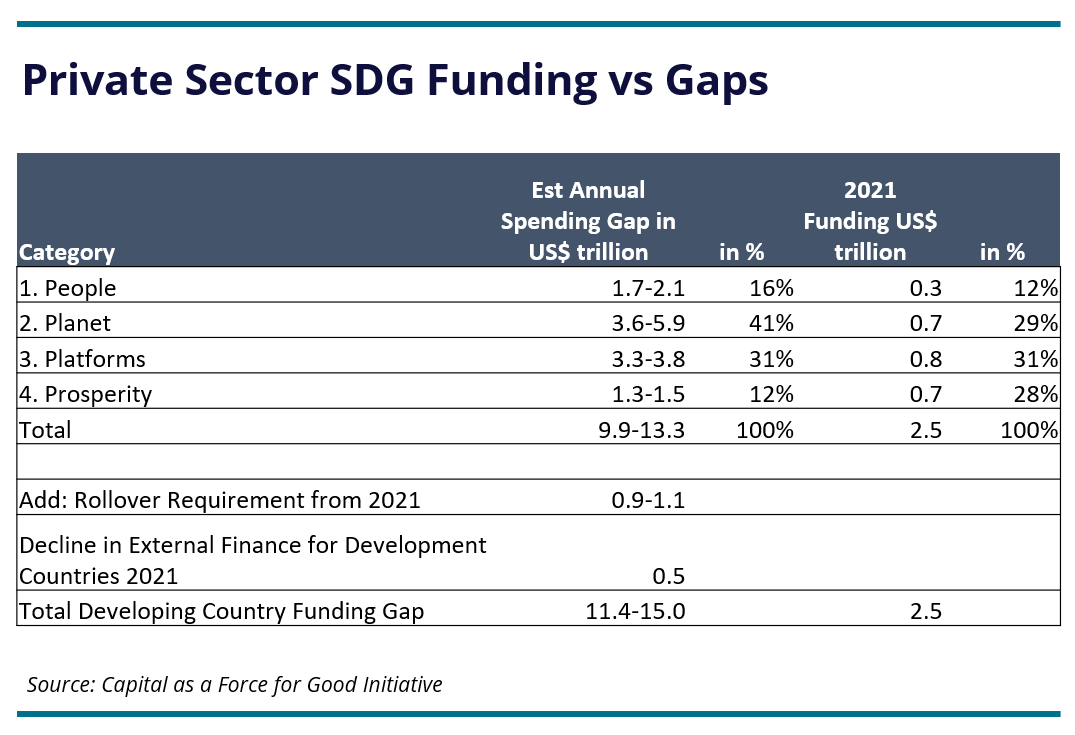

As previously stated, the total annual funding need for the SDGs has expanded to US$15-20 trillion annually, rising 30-40% year on year, faster than the private sector’s spending increases of c.20%. As a result, the annual funding gap in developing countries now runs to total of US$11.4-15.0 trillion, with significant shortfalls across all categories of spending (Table 1). The funding need of each category varies significantly with Planet related goals representing over 40% of the total funding need (given the higher estimated cost for meeting Net Zero), and People related goals counting for 16% of the funding gap.

Table 1 Finance Industry Leaders’ SDG Funding vs. SDG Funding Gaps

The increasing diversification of finance industry leaders’ SDG priorities is resulting in an alignment of their spending distribution across the different SDG categories, with the actual SDG funding need. In 2020, industry leaders’ SDG spending was still highly concentrated on Planet related goals, at the expenses of People and Platforms spending needs.

During the past year, leaders have significantly diversified their commitments across the goals and have provided nearly equal amounts to Planet, Prosperity, and Platform related goals. As before, private sector financial institutions did not provide direct funding to the fifth SDG category, Peace and Partnership (SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) and SDG 17 (Partnership for the Goals)). Given these goals are commonly seen as prerequisites for the deployment of capital, rather than as direct investment opportunities in and of themselves, they typically fall into the remit of national governments to fund (partially augmented by direct foreign aid).

The diversification in spending points to the increasing sophistication of the private sector’s engagement with the SDGs, and the critical role that private capital will play in funding them. While industry leaders clearly cannot fund all the SDGs and meet the gap on their own, a task that even if it was possible would require current spending levels to increase approximately five-fold by next year, they are becoming increasingly ambitious and innovative in deploying capital at scale across the world, pointing to the likely direction of travel for the rest of the industry, and as a result, the private sector as a whole.

5.3 Challenges remain to unlocking further capital

There are a number of challenges related to unlocking further private sector commitments in support of the SDG which need to be overcome. Following a plethora of announcements from the industry as leading institutions joined various associations, committed to Net Zero and announced their ESG policies and published impact reports, several issues have arisen for the industry to address:

-

Competing Demands on Global Capital. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent global political and economic dislocations have driven a shift in global priorities towards security at the expense of sustainability, drawing capital, resources, and attention away from the SDGs in favour of energy security, food security, and increased military spending across the globe.

-

Macro-Headwinds Repricing Assets. The perfect storm of rising interest rates, high inflation, and a global energy crisis has dislocated global asset prices, with technology stocks collapsing and oil and gas stocks rising, leading to a global redistribution of capital across sectors. Net fund flows to ESG funds and new sustainable debt issuances have both slowed down sharply in the first half of 2022, indicating that allocating to tech was the easy decision and the difficult decisions to invest for impact are still ahead.

-

A Lack of Standards for Measurement and Reporting. Despite efforts by multiple stakeholders to create standards, confusion remains about how to best measure ESG performance and how to incorporate ESG data into investment decision making, with fund managers citing it as the single biggest adoption hurdle. The lack of consistency in ESG scores, differences in disclosures, and constantly changing methodologies, among others, are creating an increasing administrative burden for many institutions.

-

Increasing Awareness of Greenwashing. The now widespread adoption of ESG systems has led to concerns on whether it is genuinely changing behaviors at these institutions or being used to put a ‘green’ or ‘sustainability’ wrapper around business-as-usual. A recent analysis by Morningstar found that c.1,200 funds (or 20% of the total), with over US$1 trillion of AUM, no longer merit an ESG label, and national regulators and authorities have begun cracking down the misuse of ESG and sustainability labels by asset managers.

-

Political Backlash Against ESG and Sustainable Investing. There has been a growing backlash against ESG from some political quarters, particularly in the United States. States with large oil interests like Texas have threatened to withdraw funds from asset managers looking to reduce their fossil exposure, while other states have prohibited their pension funds from using ESG screening at all.

-

Legal Risk Related to Fiduciary Duties. Despite a growing body of legal analysis that supports the integration of ESG into institutional investing from a fiduciary perspective, a growing number of institutions is withdrawing from international frameworks for sustainable investing based on concerns that their requirements (and specifically members’ potential inability to meet them) open these institutions to legal risks from stakeholders.

In summary, the basic challenge remains that the SDGs are seen as a “cause,” a noble and worthy one no doubt, but not as a commercially sound case to fund within the time horizons and risk levels that matter to most private sector investors. Funding the levelling up in the world through the SDGs while generating value commensurate with the requirements of investors will require the participation of a broad set of global stakeholders, both the private and public sector in a far more radical plan that can unlock tens of trillions of dollars, including funding corporations to provide technology and other solutions to address issues and create new markets.